This site celebrates the life and work of sculptor

John Cassidy (1860 - 1939).

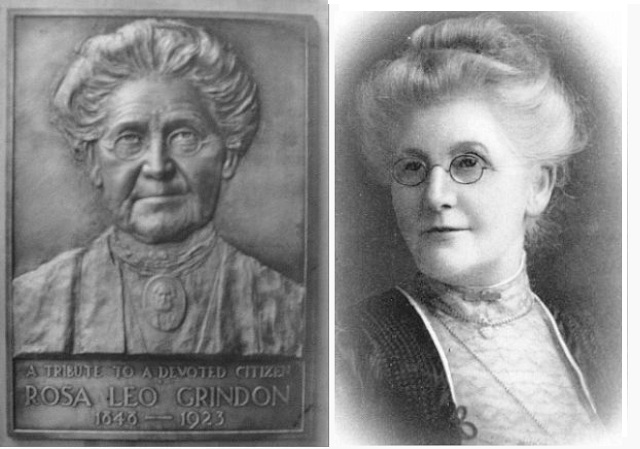

This work, a typical example of a bronze Cassidy 'medallion' appeared on the wall of the entrance hall of Manchester Central Library in 2018, apparently having been moved there from some location in the Town Hall, which had recently been closed for several years of refurbishment work.

Unfortunately, like others of its type, it has suffered from 'cleaning' which has revealed the metallic surface below the original patination, combining with the bright lighting in the foyer area where the plaque is displayed to produce an unpleasant result, especially in a photograph. The main photograph (right) is from a 1923 photograph in the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts archive; Cassidy must have worked from a portrait which we have not traced. The photographic portrait, clearly taken some years earlier, is from the book of her lectures published after her death. She wears a pendant with an image of her late husband.

We knew that the work had been made, but until 2018 had no idea of its continued existence. It was modelled by Cassidy, presumably based on a photograph, as a memorial to Mrs Grindon; exactly who, among her many friends and clubs, commissioned it we cannot say, but she has a strong connection with the Library as the large Shakespeare window there was created according to instructions in her will.

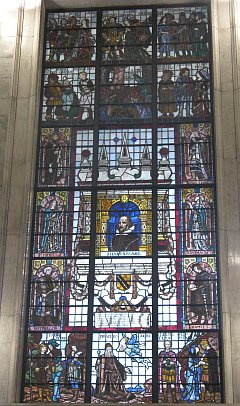

The Shakespeare window, 2018

We can see no reason why its 'temporary' location in the library should not be made permanent, and indeed why some recognition of its maker should not be placed alongside. [top]

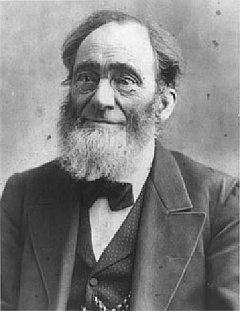

Leopold Hartley Grindon

Born in 1838, Leo Grindon came to Manchester in 1838 to work as a cashier for John Whittaker & Co,. who had a works in Radcliffe and an office in Tib lane, Manchester. His first home was no. 4 Portland Street, then a 'mean street' of artisans' houses.

He had been fascinated by Botany, especially as encountered in country walks, from childhood, in Manchester this took over his life. While still working as a cashier, he began writing on botany, country walks and other subjects, including a dozen or more books, the last published in 1885.

In 1852 he was appointed as a lecturer in the Manchester Royal School for Medicine, a position which he held for 25 years until the School of Medicine became incorporated with the Owen’s College in 1877.

In 1860 he founded, with his friend calico printer Joseph Sidebottom, the Manchester Field Naturalists Society, and remained President for the rest of his life. The Society was aimed at ladies and gentlemen who enjoyed walks in the countryside and the study of plants there; it was viewed with disdain by by the professional scientists of the long-established Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society who in 1862 blocked an application for membership by Mr Grindon.

His adherence to the ideas of the Swedenborgian Church and its Manchester minister Rev. J.H. Swinton perhaps did not endear him to academic scientists.

The 1861 census shows him living in Rumford Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, where was able to cultivate a garden, with his first wife Elizabeth, born in Blackburn in 1820, rarely is rarely mentioned in biographical writings about him.

In 1864 he left the world of commerce to concentrate on his writing and teaching, and sometime in 1883 the couple moved house to 20 Cecil Street, Greenheys, on the southern edge of Manchester, where Elizabeth died in 1892.

A newspaper correspondent in 1890 reported that he was already confined to the house. The 1891 census found the couple staying in a small hotel in the spa town of Great Malvern, no doubt for health reasons.

In 1893 Leo married Rosa, as described in the main article. Despite the chronic infirmity which he had suffered since his twenties, he had a long life; he died in 1904 aged 86. He and Rosa are buried in grave B899, Manchester Southern Cemetery.

He had no children by either of his wives.

For a much fuller biography see F.E. Weiss, 'Leopold Hartley Grindon', North Western Naturalist, Vol.5, 1930, p.16-22. Weiss was Professor of Botany at Owens College / The University of Manchester 1892 - 1930, and University Vice-Chancellor, 1913 - 1915.

[top]

The Herbarium

In 1910 Rosa Grindon passed to the Manchester Museum her husband's extensive 'herbarium' comprising dried plant samples, with notes and press cuttings for each species, and it is still consulted today by scholars who bemoan the fact that he didn't record the source of the press cuttings.

From the Manchester Museum Herbology blog:

A west-country boy with a love of the great outdoors, botany, religion, poetry and literature, much is owed to Leo Grindon. His meticulous observations offer a rare glimpse of the Manchester environment before areas were developed and many plants became extinct.

His herbarium collection is enormous. There are over 300 boxes holding thousands of specimens of flowering plants, ferns, a few fungi and mosses. Also included are the numerous botanical illustrations, newspaper/journal articles, handwritten notes, medicinal uses, and pages from key botanical works. There are also some letters found with the specimens from other collectors or botanists.

[top]

Ladies and Letters

From the Manchester Guardian, 27 September 1929

The Manchester Ladies' Literary Society, which opened its winter session this afternoon, has now more than a quarter of a century's activities to its credit. It had its roots in a little friendly circle in the home of the late Mr. and Mrs. Leo Grindon. Mrs. Grindon, who had been for many years an ardent helper in her husband's enthusiastic botanical work, was always endeavouring to turn such gatherings as these, however small they much be, to some practical account, and came to the conclusion that there was no reason why her own sex should not have a literary society of its own.

So the Manchester Ladies' Literary Society was formed, and at first was in the habit of holding its meetings in Mrs. Grindon's home in Cecil Street. At one time it had as many as forty active members and thirty associates. After Mrs Grindon's death the members paid tribute to her memory by renaming the Society "The Rosa Grindon Literary Society"; but with the passing of years and old members and the coming of new it was through desirable last year to revert to the old title. The afternoon meetings, which are held monthly, are usually devoted to addresses and discussions on literary and social subjects. The current president is Miss C.E. Andrews, minister of the New Thought Church in Raby Street, Moss Side.

[There had been an earlier version of a Manchester Ladies' Literary Society, founded by botanist and suffrage supporter Lydia Becker (1827-1890) in the 1860s, which despite its name also dealt with scientific matters.]

[top]

Lighting a fire

Extract from a letter by Rosa Grindon published in the Manchester Courier, 1907Sir,- No work in Manchester can be greater or more important than the cleansing of the air we breathe, and to this end every individual can do something when he knows how; but such knowledge does not come naturally to man. Man had to be taught most things that pertain to his highest good, and this is one of them. Yet what teaching do we have? The manufacturer is taught by fines and regulations, but the average domestic man or woman is left without guidance unless their chimneys get on fire. Then they are sharply taught that chimneys require sweeping. But could not the Education Committee or the Sanitary Committee appoint a competent man - the more enthusiastic the better - to give public lectures and practical demonstration on the art of "making and mending" the domestic fire. No amount of verbal instruction only would be effectual. The lesson must be demonstrated by the actual laying of the materials at the start in their proper cone-like shape as well as the slow and frequent feedings afterwards.

The schoolrooms where cooking lessons are given could easily be available for the purpose. The subject of the most successful method of starting a domestic fire is one of more than economic interest to all women. It is often a matter of great urgency in a household, and yet some women have "no luck" as they call it, when it is but knowledge that they require. So simple a thing as that coal should be placed with its "grain" pointing up the chimney is not so generally understood as some people may imagine; one might talk a long time before the why and the wherefore would be grasped, whereas a Bunsen burner applied to one piece of coal with the grain horizontal and to another piece with the grain placed vertically would demonstrate in a few minutes the advantages to be gained in the rapid burning of coal beyond its smoking stage when the fire is started or being fed.

[top]

Website created and compiled by Charlie Hulme and Lis Nicholson, with the invaluable assistance of the John Cassidy Committee, Slane Historical Society.

Rosa Leo Grindon (1923)

Life | Shakespeare | Flowers | Suffrage | Cecil Street | Herbarium | Leo Grindon

Rosa Leo Grindon was born in 1848 as Rosa Elverson in Newhall, a village in the far south of the country of Derbyshire. Her father William Elverson and mother Jane (née Haynes) were also natives of the village, as were her sisters Mary and Alice and her brother William Henry. The 1851 census shows their address as a cottage on Maypole Hill, Newhall, with William (senior) aged 33, working as an agricultural labourer. However, by 1857 he was listed in a directory as a 'general dealer' and in the 1861 census as a 'draper and grocer.' The family was still together at that time, including a new daughter, Clara. Oddly, we have not been able to trace her father on the census beyond 1861.

Rosa's brother William Henry Elverson went on to establish a successful brickworks in the nearby town of Stapenhill, near Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire. Her sister Alice moved to London to be governess to the daughter of a solicitor, John Vallance, whose wife had died. In 1896 she married his son John Daniel Vallance; Alice Vallance was later named as an executor of Rosa's will.

It appears that Rosa attended Cheltenham Ladies College, a famous boarding school, and by 1871 she had made her own way in life and was living, aged 22 in Stafford, as a 'companion' to an 88-year-old widow, Isabella Leighton Morgan, who died in 1873. By 1881 Rosa was living in the Stockport area, employed as housekeeper at Torkington Lodge, home of the wealthy landowning Barlow family. While working in domestic roles, Rosa studied for a diploma awarded by the University of St Andrews and known as the Lady Literate in Arts (L.L.A.) which was considered the equivalent of a Master's degree and could be earned by what today is know as 'Distance Learning.) In 1883 she gained a diploma in botany, political economy, and physiology. She write a memoir of her father, which seems not to have been published.

In 1891 she was in Lichfield, Staffordshire as 'Lady Housekeeper' to a brewer, John Gilbert, at 6 Beacon Street, Lichfield. John Gilbert was appointed Mayor of Lichfield in 1892 and 1893, and being a widower he chose Rosa as his Lady Mayoress. While in Lichfield, she worked on the transcription of some medieval manuscripts found in the Cathedral library, under the aegis of the 'Text Society', apparently a reference to the Early English Text Society. Her co-worker in this project was John Gilbert's daughter Florence.

It was in Lichfield that she met a friend of her father, Leopold Hartley Grindon, and they were married in 1893. Leo, as he was generally known, was thirty years her senior, born in the Bristol area in 1818. He had been living and working in Manchester, latterly as a lecturer and author since 1838. Rosa joined him in his Georgian terraced house at 20 Cecil Street, where the 1901 census also lists their two domestic servants Maud and Lily Renshaw. Rosa styled herself Rosa Elverson Grindon - an early adopter of a present-day style - until after Leo's death in 1904 she commemorated him by adopting the name Rosa Leo Grindon by which she was better known in Manchester.

In Manchester Rosa took part in many activities, and founded a number of societies including groups devoted to botany and Shakespeare, as well the foundation of a chess club for ladies. In her last years she became an adherent of spiritualism, perhaps in the hope of contacting her late husband. After Leo's death she remained in Cecil Street, attended by a series of female servants, until her death in 1923. [top]

Shakespeare

After her marriage Rosa continued her and her husband's interest in literature, in particular the works of Shakespeare. After her husband's death she published a series of small books of commentary on individual plays, based on her popular lectures, which were combined after her own death into a volume entitled Shakespeare and his Plays from a Women's Point of View published in 1930 by the Policy-Holder Journal Company of Manchester, from which the portrait photograph on this page is reproduced.

As a memorial to her husband, she funded the creation of a large stained-glass window featuring Shakespeare and scenes from his plays, designed by Arts & Crafts artist Robert Anning Bell RA (1863-1933), and was completed just before his death. It was installed in the entrance hall of the the new Manchester Central Library, opened in 1934; she died a decade before it was completed, but she left £1000 in her will for the making of such a window, on condition that the planned building of a new central library began with ten years of her death. By the time the building of the Library began after many delays, interest had increased the sum to £1300, and the extra was used in addition for two heraldic windows by George Kruger Gray. The project went ahead after some delay due to a court case raised by Rosa's executor Sir Harold Elverston (not Elverson - no relation - he was known to Rosa from the Shakespeare connection). She also left her collection of books on Shakespeare to the Library Committee, and established a prize awarded to students at the Royal Northern College of Music for the best composition to accompany a Shakespeare text.

Detail of the Shakespeare window.

Rosa became a friend of Frank Benson (another Cassidy subject), an actor-manager who specialised in Shakespeare works and organised a series of Shakespeare Festivals at Stratford-on-Avon. He invited her to lecture at the festival, which she did, in 1909 (on Cymbeline), 1910 (on Hamlet), 1911 (on Othello) and 1913. These were the culminating years of the women's suffrage movement, of which Rosa was a supporter, and her views on Shakespeare have been quoted by feminist writers down to the present day. Susan Carlson, writing in 1996, quotes from her lecture on Othello:

These matters should be investigated by women on behalf of women, for the stigma on Desdemona rests on women to this day, and in certain circles this supposed lie of Desdemona was brought forward as an argument that Shakespeare knew that a woman's word could not be trusted.Ms Carlson comments:

While this recognition of the impact of gender on criticism is familiar enough to us at the end of the century, Grindon's feminist manifesto was received with some hostility in her time, even though she was a regular lecturer at the festival.A fellow lecturer at the 1911 Festival was famous actress Ellen Terry, who also proposed a re-interpretation of the role of Shakespeare's women.

Rosa was a great supporter of The Merry Wives of Windsor, at the time considered by critics a s one of the weakest of the Bard's works. She lectured many times on this and other Shakespearian matters to groups and societies in the Manchester area, and at the University. An obituary mentions the 'Manchester Ladies Literary and Scientific Club' of which she was President, although we cannot trace any mention of this body.

On behalf of the Tercentenary Association, which she founded, she created a 'Shakespeare Library and Museum' collection, intended to be donated to the city library, in the Cecil Street house. Selections from the plays were staged in the back garden of the house, and there were great plans to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the death of Shakespeare. The exhibition opened on 13 May at the Memorial Hall, in Albert Square, and included among other items early editions of the works, manuscripts, portraits of actors, a model of his birthplace and a much larger model of the Globe Theatre made by Richard Flanagan of the Queen's Theatre. Among items planned to be shown in the exhibition was a 'bronze bust of F.R. Benson, by Mr Cassidy', but this is not mentioned in press reviews. There were also exhibits in the Milton Hall, and the John Rylands Library held its own exhibition. Rosa combined two of her interests by arranging for a 'Shakespeare Garden' featuring plants known in Shakespeare's time, based on a similar garden in Stratford - and initially with some plant cuttings taken from there - which is still maintained in Platt Fields Park.

Reference: Susan Carlson. 'The Suffrage Shrew: The Shakespeare Festival, "A Man's Play" and New Women. In Shakespeare and the Twentieth Century.' In: Selected Proceedings of the International Shakespeare Association World Congress, 1996. London: Associated University Presses, 1998. [top]

Flowers

Rosa was supportive of her husband's botanical work, and continued to further the cause after his death. In his later years, Leo was too unwell to engage in field activity, so she (no doubt with some help) transformed the back yard of 20 Cecil Street into a garden for his enjoyment. In 1905, after his death she formed the 'Mrs Leo Grindon Flower Lovers' Guild'. The rather remarkable picture above shows a meeting of the Guild in her garden, with Rosa in her black dress on the right.

She went on to encourage working-class people to do the same, including competitions among tramway men and residents of Manchester Corporation's Blackley estate for the best back-yard garden. One of the Blackley residents whose involvement has been documented was James Hapgood (1863-1924) of 105 Old Road; the photographs in his collected have been passed down the family and are reproduced here from the Hapgood website under the terms of a Creative Commons licence.

This photograph was taken on a ramble at Stamford Park, Altrincham and (like the view above) includes James Hapgood, second from left on the back row. (Incidentally, the Hapgood website records that while working as a bricklayer in 1892, Mr Hapgood survived a fall of two storeys during the construction of the John Rylands Library.)

Also known to be a member of the Guild, and winner of a specially-struck medal presented by the Lord Mayor, was Richard Rennison, a tram motorman. Born in Ouseburn, Yorkshire, in 1911 he lived in what had been a draper's shop run by his wife at 18 Rochdale Road, Blackley with his wife Eliza Ann and 'adopted son' Edward Machin. The 1911 census concerned itself with child mortality, and their entry, written by Eliza, records that in 29 years of marriage they had six children, all already dead. Ernest Machin Rennison was caught up in the World War, and was reported missing in action, presumed dead, in 1917, and Eliza in 1922; both are listed on a gravestone in Newport, East Yorkshire. Richard died in 1930.

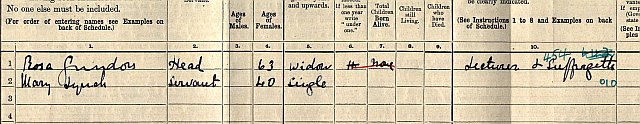

Suffrage

Rosa was, as might be expected, a supporter of the campaign for votes for women, although perhaps not from its earliest days. She is recorded as attending, from 1909, meetings of the North of England, and Manchester, Societies for Women's Suffrage, one of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She wrote 'Suffragette' in her entry on the 1911 Census, rather than boycotting or spoiling the form as some did, and there is no evidence that she supported the militant activities associated with the 'suffragette' name in the 1911-14 period such as arson, damaging art works, or planting bombs. It's hard to imagine that she approved, for example, of the bomb damage to the Cactus House in Alexandra Park on 12 November 1913. [top]

Cecil Street

The Grindons' home in Greenheys, marked red on the 1908 map above, was in a three-storey Georgian-style terrace called 'Dorking Terrace', built in the 1850s when the area was a middle-class suburb. 'Cecil' was the family name of the Earls and Marquesses of Salisbury. This may not be the source of the street name, although not far away adjacent to Oxford Road station there is a pub called 'The Salisbury' which claims to commemorate the same family. Leo and Rosa's neighbours in 1901 were William James, a Welsh Calvinistic Minister, at No.18 and John Hope, a tailor and draper, at no.22. Every house in the row had at least one live-in servant.

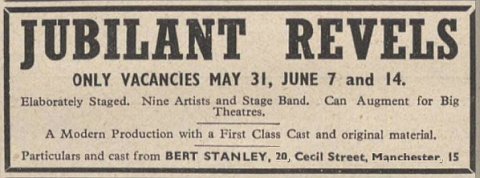

In its later years, the middle-class moved further out of the city, and the houses of Cecil Street, often divided, were home to the less wealthy. The 1939 Register shows two households in No.20: on one part Bartholomew Wrenn, a 'trainee aero-fitter' with his wife and baby, and in the other part two 'travelling variety artistes', Gladys Wright and Florence Hughes.

It appears that they were members of a Concert Party called 'Jubilant Revels' run by Bert Stanley (a man whose fame has yet to spread to the Google database), as this advert from The Stage in 1937 reveals. Would Mrs Grindon have approved?

No. 18 next door had no less than seven separate households, one of them a housekeeper.

By the 1960s the houses were in ruinous condition; this picture shows one of the Cecil Street terraces, in their final days before demolition. Was the gap due to bomb damage, the start of demolition, or just collapse?

In the early 1970s this part of Cecil Street was totally cleared; the original northern end no longer exists and the site of no. 20 is in 2018 part of a car park (above) on the edge of the University campus, while to the south, some modern houses have been built. [top]

The content of this feature came from many sources, including Ancestry.co.uk, the British Newspaper Archive, the Guardian online archive, Manchester Libraries image collection, Google books, Old-maps.co.uk, The University of Manchester Library, the Hapgood website and (by kind permission) and the archive of the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts, as well as blogs by Tony Shaw, Herbology Manchester and Adele Emm. Full texts of several Leo Grindon books are available on line, including Project Gutenberg, Google books and archive.org.

Written by Charlie Hulme, November 2018. Comments welcome at charlie@johncassidy.org.uk