This site celebrates the life and work of sculptor

John Cassidy (1860 - 1939).

The name of Joule is known by everyone who has ever studied science at school, as it was chosen as the name for the SI unit of work and energy; very appropriately as James Joule's greatest work was to quantify the equivalence between energy in its various forms. Joule died in 1889, and that year an international conference decided to use his name for a unit - initially defined as the energy dissipated in one second by current of one ampere flowing through a resistance of one ohm. In 1960 it was confirmed as the official SI Unit for energy in all forms, officially the amount of work done when a force of one Newton moves through one Metre. It is also used to measure an amount of heat, although the use of the Calorie (kcal) - originally the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1 °C - lives on, controversially, especially in contexts of energy derived from food, although now defined simply as 4184 joules.

James Prescott Joule was born in the house adjoining the Joule Brewery in New Bailey Street, Salford, on 24 December 1818, the son of Benjamin Joule (1784 1858), a brewer.

His early schooling was by home tutors in the family home 'Broomhill', Pendlebury, near Salford, then in 1834 he was sent, with his elder brother Benjamin St John Baptist Joule (who later became known as an organist and composer of music, and 1861 bought Tory Island, off the coast of Donegal in Ireland), to study under Manchester's other famous scientist John Dalton at the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, in 1850, he was made president of the Society.

He became the manager of the family brewery until it was sold in 1854, leaving him with more time for scientific research. ('Paddy's Goose' in Bloom Street, Manchester, near the coach station, originally The Fleece, is said to be the only surviving pub which once served Joule's ales.)

A great deal has been written about Joule, his experiments and his discoveries in the field of electricity, heat and energy, there is little point in summarise his career in any detail here: Wikipedia's article forms a useful starting point, as does D.S.L. Cardwell's biography.

Put simply, he established that mechanical work and electrical current generated heat, and that there is a fixed ratio between the various forms.

On the Joule trail

His childhood home, 'Broomhill' in Pendlebury (marked above on an 1893 map) has vanished under suburban development, including a street named 'Broomhill Road.'

In 1843 the family moved house from Pendlebury to 'Oak Field', Upper Chorlton Road, Whalley Range, on the south side of Manchester, shown on the 1848 map above. Benjamin Joule (senior) had a laboratory built there for his son; there he carried out his famous experiment with a paddle-wheel in a bucket to establish the amount of heat generated by work. The house no longer exists; sometime between 1908 and 1920 it was demolished and replaced by a small estate of semi-detached houses, typical of the period, with streets named Whitethorn Avenue and (appropriately) Oakfield Avenue, which still stand today.

In 1847 James Joule married Amelia, daughter of Mr. John Grimes, Comptroller of Customs, Liverpool. They initially lived with Joule's father at 'Oak Field' but in 1849, before the birth of their son Benjamin Arthur Joule in 1850 they moved into no. 1 Acton Square, The Crescent, Salford, which still exists, opposite the Salford Museum and Art Gallery. The house, one of a row of three Georgian town houses built on the corner of Crescent and Acton Square, is now shared by the Centre for Applied Archaeology and the University of Salford Centre for Sustainable Urban and Regional Futures (SURF).

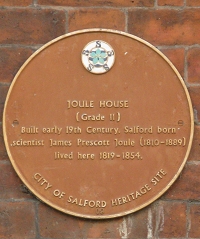

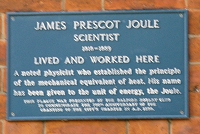

The plaque mounted on the elevation to 'The Crescent' of the building states that Joule 'lived there 1819 to 1854' which seems to contradict other sources.

A plaque on the Acton Square side, presented by the Rotary Club, curiously exhibits a variation on his middle name.

Tragically, his wife Amelia Joule died early (1854), leaving him with one son and one daughter; a second son, Henry James, had died in infancy in 1854. It seems he then moved back into 'Oak Field' for a while.

In 1861 (1858 in some sources) he moved with his family to 'Thorncliffe' (or 'Thorncliff') on the Stretford Road, in Old Trafford, close to its junction with Chester Road, just under three miles from Manchester City Centre, a house built on land which had been sold by the de Trafford family in 1849. The map extract above, from 1891, shows the location, opposite the Manchester South Junction and Altrincham Railway (now part of the Metrolink tram system). It lies just outside the boundary of the City of Manchester.

The previous resident appears to have been John Haworth, one of the pioneers of tramways in the Manchester area. He gave 'Thorncliff' as address on his Patent application for a method of building 'tramways in ordinary streets and roads'. The Patent was granted in 1860, and involved a wheel central guide rail which would keep the main wheels on flat rails either side, of the vehicle but in the event his design was passed over by the Manchester Carriage Company in favour of the simpler system of street tramway still used today.

At 'Thorncliffe' (pictured below and in the main text) Osborne Reynolds relates that Joule unfortunately ran into trouble with the neighbours, who objected to his steam engine.

James and Benjamin Joule sold the house in 1868 to Frederick Jardine, of Kirtland & Jardine, organ builders, a firm still in business in 2012 as Jardine Church Organs. By 1895 the householder was John James Kent Fairclough, anaesthetist at the Victoria Dental Hospital in Manchester.

From 1907 until around 1910, 609 Stretford Road was the home of William Furber and his family, including his widowed daughter Ella Smith and her daughter Dorothy 'Dodie' Smith (1896-1990), famous for her novel, made into a Disney cartoon feature, One Hundred and One Dalmatians. She, rather than Joule, is commemorated by a 'blue plaque' on the building, with the quotation 'It was so quiet and semi-rural that the corncrake could still be heard' - above the noise of passing trams, trains and ships, presumably.

The 1901 Census gives their address as 586 Stretford Road, which was the Kingston House' mentioned in biographies of Dodie Smith. This house was demolished c. 1907 to make room for widening of the railway cutting, and the family moved to 'Thorncliffe'.

Dodie Smith moved to London when her widowed mother married again, and went on to have a long career as a playwright. She revisited 'Thorncliffe' in 1958: her biographer Valerie Grove describes the experience: 'Thorncliffe still stood, black with dirt. There was a solicitor's office on the first floor, in her grandmother's bedroom, so the room once papered in rosebuds and satin stripes was now Dickensian with dusty files.'

'Thorncliffe' has survived many changes in the Old Trafford area, latterly as offices for a series of organisations. In 2012, following some sprucing-up, under the name of 'Democracy House' it is the home of the Black Health Agency.

The row of houses then known as Cliff Point, his next home, apparently still exists, within a Conservation Area (picture above from Google) although the house numbering now follows that of Lower Broughton Road; further investigation is needed to establish which one was the Joule home. Still at this adress in 1877, he was awarded a pension by the Government in recognition of his discoveries.

Later that year he moved is familty to their final home at 12 Wardle Road, Sale, Cheshire. (the view above is from the Trafford Lifetimes website) In the 1881 Census he described himself as 'DCL, LLD, Physicist' and his household included his unmarried elder sister Mary ('assistant') and his son Benjamin Arthur Joule, described as Artist (Painter.) Also resident were Sarah Coward, cook and Mary Adshead Hewitt, housemaid.

Joule's children

James's son Benjamin Arthur Joule's career as a painter does not appear to have brought him fame; he pops up the 1901 census as a guest in a hotel at 28 Bath Street, Waterloo, near Liverpool, describing himself as 'living on own means.' In 1911 he described himself as 'married for 10 years', yet he was living in a boarding house at 44 Princes Street, Southport with no sign of a wife.

However, one writer states that he had a son, Frederick, born in 1869 (yet in 1871 Benjamin was living at home and a student at Owens College), and died in 1948, and that Frederick married and had several children.

Benjamin died in 1922, and the Manchester College of Science Technology (later UMIST and now part of the University of Manchester) bought what remained of his father's scientific apparatus, some of which is now on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester.

James Joule's Daughter Alice Amelia Joule married John Clement Joule (a distant relative?) in 1879, and their daughter Lilian Alice Mary Joule, born in 1885, married Frederick William Thomson, manager in a Patent Medicine Company, in 1906. In 1911 they were living on the Wirral Peninsula at 15 Malpas Road, Wallasey, a semi-detached house which still exists in 2009. They do not appear to have had any children.

Joule is commemorated in Manchester by a statue in the entrance of the town hall, opposite a statue of another great Manchester scientist, John Dalton. The illustration shows Joule's head from the Town Hall statue, which is by Alfred Gilbert (1854 -1934) and dates from 1893. Gilbert was one of the greatest sculptors of the era: he created the famous work known as 'Eros' in Piccadilly Circus, London.

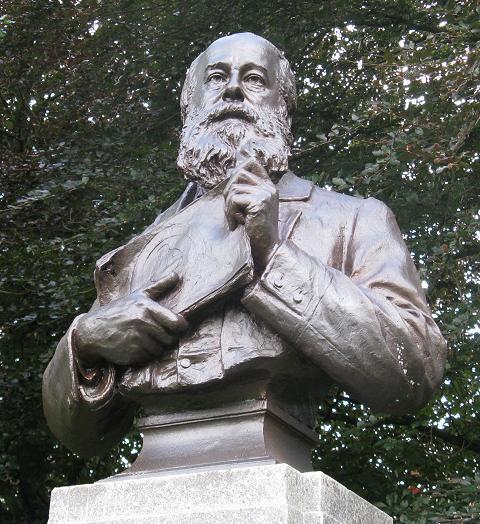

James Prescott Joule, Worthington Park, Sale (1905)

It was 1901, some years after his death in 1889, and eight years after the statue of Joule by Alfred Gilbert had been unveiled in Manchester Town Hall, that a proposal appeared to create a memorial in Sale, Cheshire, where Joule had lived from the 1870s. The suggestion was to build a 'tower to be used for meteorological observations' in Sale Park, which had been created in 1900 on land donated to the town by a wealthy local Widow, Mrs Mary Worthington. Mrs Worthington donated £100, and contributions were received from scientists around the world. However, the money raised was not enough for the proposed tower, and not much happened until the fund was re-launched with Dr Charles Herbert Lees (1864-1952), then of the Physics Department of the Victoria University of Manchester, as chairman, this time with the memorial to be a bust, which would be created by John Cassidy.

We are fortunate in having this picture of Cassidy with the clay model for the bust, more or less complete, in his Lincoln Grove studio, probably early in 1905 - from the proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

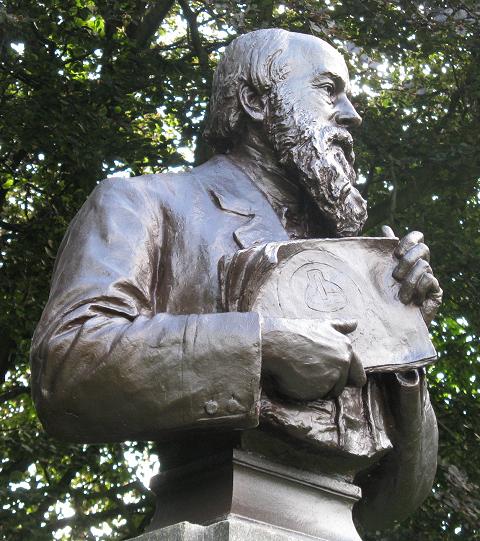

The Manchester Guardian of 7 April 1905 (page 5) has a picture of the clay model and reports: 'The work has been entrusted to Mr John Cassidy, the well-known sculptor, of this city ... Mr Cassidy has succeeded in giving much character to the head and face, and there is a great deal of detail in the work. Joule is represented as reading to the audience a scientific paper, the subject of which can be guessed from the diagram upon it, illustrating his famous "tangent galvanometer." The expression of intellectual absorption in his theme is happily conveyed. Although Mr Cassidy's work in the clay will soon pass into the hands of the bronze founders, it is not expected that the unveiling ceremony will taken place before the beginning of next month.' In the event, several months passed.

|

IN MEMORY OF DR.

JOULE.

Unveiling the Monument at Sale. Manchester Evening News, 28 October, 1905. The memorial to the distinguished physicist Dr. Joule, which has been erected by subscription in Sale Park, was unveiled this afternoon by Sir William Bailey, president of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. The memorial is in the form of a bust mounted on a pedestal, and a suitable inscription records the fact that Dr. Joule died at Sale after living there for a number of years. The afternoon's gathering included a large number of scientific men from Manchester and elsewhere, professors at Victoria University, and members of the Sale District Council. The monument was unveiled by Sir William Bailey, who, on behalf of the subscribers to the memorial fund, handed over the statue to the chairman of the District Council (Mr John Davis), "to perpetuate the memory of the late Dr. James Prescott Joule." In the course of an eloquent tribute to the memory of Joule, Sir William mentioned the fact that he was born in New Bailey Street, Salford, in the year 1818 and that he studied under Dalton, the celebrated discoverer of the atomic theory. His great discovery was the "mechanical equivalent of heat." He determined the relation between units of heat and energy, by his various methods, and he declared the rate of exchange - the bank rate - between heat and work. The gift of the monument was gratefully accepted by Mr. Davis on behalf of the town of Sale, and a vote of thanks to Sir William was proposed by Mr. Alfred Hopkinson, Vice-Chancellor of Victoria University. This was seconded by he Rev.Canon Jones, and carried with applause. |

The bronze bust stands today on its stone plinth in a pleasant garden within the park, which was renamed Worthington Park, after the donor, to celebrate its jubilee in 1950. The Park is off Cheltenham Avenue in Sale. (Map)

Cassidy had to work from pictures of Joule, who had died 25 years earlier.

Cassidy's signature can be found on the back of the bust: 'John Cassidy Sculp 1905'.

The Tangent Galvanometer was a device used by

Joule to measure electric current. The original device,

shown to the left, is now in a museum in Glasgow: it

consists of a magnetic compass set inside a coil of wire

through which current is passed. The greater the current,

the more the compass needle will be deflected from its

normal north-pointing position.

The Tangent Galvanometer was a device used by

Joule to measure electric current. The original device,

shown to the left, is now in a museum in Glasgow: it

consists of a magnetic compass set inside a coil of wire

through which current is passed. The greater the current,

the more the compass needle will be deflected from its

normal north-pointing position. James Joule suffered from a deformity of the spine, and in his later years was in poor health. He died in 11 October 1889, and is buried in Brooklands Cemetery, Sale, Cheshire.

His gravestone, it is said, carries the number 772.55 and a quotation from the Gospel of St John, "I must work the works of Him that sent me, while it is day: the night cometh, when no man can work" (9:4). 772.55 was the number established by Joule of the Mechanical Equivalent of heat, established in old-style units as foot-pounds per British Thermal Unit.

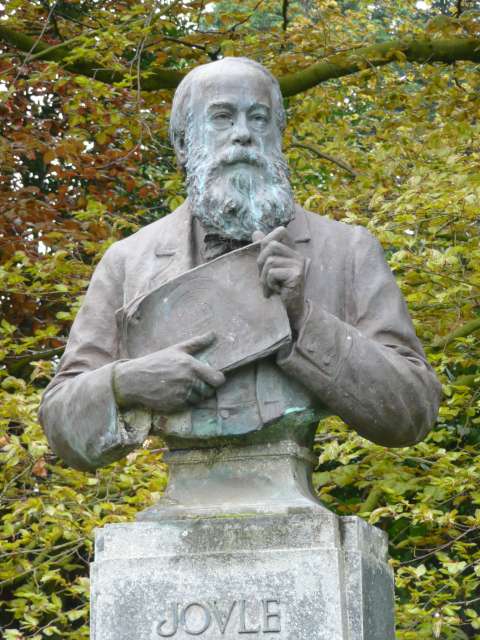

The pictures originally included with this feature showed the work as it was in 2008. We have retained one (above) to show the condition such works can fall into if not cleaned. Fortunately, bronze is basically resistant to corrosion and can be restored to almost-new condition by sympathetic cleaning, as our other pictures, dating for 2009, illustrate. The use of 'V' for 'U' is a convention dating from Roman times when the letter 'U' did not exist ... but neither did 'J'.

Joule's homes today

Looking down New Bailey Street, Salford from the top deck of a bus, 2012. The train is entering Salford Central station. The buildings on the right are on the site of the Joule Brewery; to the left was the New Bailey Prison which closed in the 1860s, the site later becoming a railway goods yard.

Above, No.1 Acton Square, in 2012. This is a large house: there is another frontage of equal width round the corner in The Crescent, and more of the building, off to the right of this picture. A testament to the money to be made from brewing beer, perhaps, although the 1851 census lists only two live-in servants. Joule would have had plenty of space in the cellars for his experiments.

In 1950, a Joule Museum was established in this building, displaying artefacts and documents from collections including that of the Tappenden family, relatives of Joule. This closed (at a date yet to be established - can you help?) and the artefacts passed to the UMIST Museum of Science and Technology and its successor the Museum of Science and Industry (MOSI) in Liverpool Road, Manchester. The manuscripts and documents, along with others, passed to UMIST Library and now held by the John Rylands Library, Deansgate, A comprehensive description of the collection can be found on the Library's 'ELGAR' archives database.

The University of Salford bought the building from Maidments Solicitors (who moved to 22 The Crescent) in 2011, and it was stated in a press release that 'Salford University plans to open an educational "outreach room" displaying original scientific apparatus used by Joule to inform people about the important experiments conducted at the site.' This has materialised as a display room in the reception containing objects used by J P Joule, on loan from the Museum of Science and Industry, with an information panel for visitors to browse. (Viewing is by appointment only.) The wording 'Joule House' which, until recently, appeared on the entablature above the door, has been removed possibly to avoid confusion with the new Joule House data centre - see 'memorials' below.

Around the corner, 48 and 49 The Crescent, forms part of the same building, as shown in the picture above. Both now form part of the University along with 1 Acton Square.

'Thorncliffe' - 609 Stretford Road - still standing in 2012. The blue plaque commemorating Dodie Smith is above the door. After selling 'Thorncliffe' the family moved to 5 Cliff (or Cliffs) Point, Lower Broughton, Salford with his older brother Benjamin, his son, Benjamin Arthur, and other family members.

Joule's house at 12 Wardle Road, Sale - once called 'Rutland House' - still exists (unlike some other other Victorian villas in the Road) and has been named 'Joules House' by its current (2012) owners, Creative Support, who provide residential accommodation for people with mental health problems. It was built in 1867; the first inhabitant was John Williamson, who moved with his family in 1877 to a new house next door.

St Paul's Church in Sale has a brass plaque on the pew used by Joule, seen in the picture above.

TO THE GLORY OF GOD

AND IN MEMORY OF

JAMES PRESCOTT JOULE

WHO USED THIS PEW

-----------------------

He was eminent as a Scientific

----- Investigator. -----

BORN 1818 AT SALFORD

DIED 1889 AT SALE

AND IN MEMORY OF

JAMES PRESCOTT JOULE

WHO USED THIS PEW

-----------------------

He was eminent as a Scientific

----- Investigator. -----

BORN 1818 AT SALFORD

DIED 1889 AT SALE

The hassock, depicting one of Joules mechanical equivalent of heat experiments, was made in 1989 for the centenary anniversary of his death.

Other memorials

Recently, and most appropriately in light of his brewing career, the name 'the J.P. Joule' has been given by the JD Wetherspoon company to a pub opened in 1997 in Sale town centre.

In London, Joule is commemorated by a white marble tablet in the North Choir aisle of Westminster Abbey, in company with other famous scientists.

The Joule Library, in the Sackville Street building of the former University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), which has been part of The University of Manchester since the 2004 merger of the two institutions in 2004, UMIST was a successor to the Mechanics Institution founded in Manchester in 1824, a year now quoted by the University as the date of its establishment.

More recently, the name 'Joule House' has been given to a large 'Data Centre' building in the Trafford Park Industrial Estate.

Appendix 1: Pronunciation

The name 'Joule' can be, pronounced in at least three ways, rhyming with 'fool', 'fowl' or 'foal.' The present writer knew a family in Derbyshire who definitely referred to themselves as 'Joal.' 'Jool' - is the accepted pronunciation for the name of the famous scientist, the SI unit, and the Library named after him at The University of Manchester. Some have claimed that this is a French pronunciation, which James would not have used.

However, what might be seen as a definitive statement, and certainly relevant to this article, would appear to be that in a letter from Professor Lees, published in Nature, Vol. 152, 602-602 (20 November 1943):

If the desire is to

pronounce the name as it was pronounced by the family and

by the friends of Dr. Joule, there can be no doubt it is

'Joole', so as to rhyme with cool, tool or rule.

Professors of the University of Manchester, in the

eighties of last century, such as (Sir) Henry Roscoe,

Balfour Stewart, (Sir) Arthur Schuster and Osborne

Reynolds, all friends and some close friends of Dr. Joule,

all pronounced his name in this way. Forty years ago, when

as chairman of a committee for erecting a memorial to Dr.

Joule in Sale Park, I met his son, Mr. B. A. Joule, he

told me 'Joole' was the right pronunciation, and that in

old family deeds the name was written 'Youle', like the

name of the village Youlgreave in Derbyshire in which the

family lived. It would be interesting if the upholders of

the pronunciation 'Jowl' would cite their authorities.

Appendix 2: Sale

Sale is an old township - now in the borough of Trafford but historically in Cheshire - on the Bridgewater Canal, five miles from Manchester. By the time Joule moved there it had become a busy commuter suburb, thanks to the frequent train service provided by the Manchester South Junction and Altrincham Railway, which a century later became part of Manchester's Metrolink light-rail system.

Appendix 3: Beer

Although Joule's Manchester brewery closed down in the nineteenth century, the name remained associated with beer for many years afterwards thanks to another branch of the family. Francis Joule, born in Youlgreave, set up a brewery in the town of Stone, Staffordshire in the eighteenth century. It passed to his son, who sold it in 1873, but the new owners kept the name of Joule's. It became part of the large Bass Charrington group in 1970 and production in Stone ceased four years later, although some of the buildings are preserved. Thanks to www.thepotteries.org for this information.

Web Links and Bibliography

Joule in Wikipedia

Sale and Altrincham (the Luso Pages)

Friends of Worthington Park

Crosbie Smith, Joule, James

Prescott (18181889), Oxford

Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University

Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/15139,

accessed 2 Oct 2012] (Login required.)

Donald S.L. Cardwell, James Joule A biography (Manchester University Press, 1989) (Preview on Google Books)

Osborne Reynolds, A Memoir of James Joule (1892). Reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Terry Wyke, Public Sculpture of Greater Manchester p. 394 (Google Books preview)

Valerie Grove, Dear Dodie: the life of Dodie Smith (London: Chatto & Windus, 1996.)

Thanks...

... to Brenda and Philip Scragg for the pictures of the bust, to Michael Riley, Parish Archivist for St. Pauls Parish Church, for the picture and information about the pew, and to Dr Michael Nevell for information about 1 Acton Square.Written by Charlie Hulme, February 2009. Updated October 2012.