This site celebrates the life and work of sculptor

John Cassidy (1860 - 1939).

James Gresham, by John Cassidy (1904)

We are fortunate that the life and work of James Gresham was chronicled by his grandson Colin A. Gresham in a small but essential book James Gresham and the Vacuum Railway Brake published in 1983.

Colin Alastair Gresham (1913-1989) was the son of James Gresham's youngest son, Frank James Gresham. He lived in Criccieth, North Wales, and wrote extensively on the history and archaeology of the Criccieth area; he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Wales in 1969.

In compiling this page, we have relied heavily on Colin Gresham's book, which contains much on his engineering inventions and some notes about his art collection, as well as family history and some anecdotes and family legends.

Two examples follow:

We read that, when a teenager, he persuaded the local cemetery to commission a picture of their premises, and included a small dog for artistic effect. The clients then refused to pay on the grounds that dogs were not allowed in the cemetery.

On a trip to India in 1892 with the second Mrs G. to inspect their works there, he was, the tale runs, approached by the captain of the ship who had heard he was an artist. Another passenger, a prince of Siam, was to disembark at Bombay, and the ship was required to fly the flag of Siam, a complicated affair with a white elephant on a red background, which was not available on board. James and Helen made one up with material from a red ensign and a white tablecloth, and protocol was satisfied.

However, having been written, perhaps partly from memory, at the age of 70, the book does suffer from some errors. The dates of James's home in Old Trafford do not agree with Census records, and Gallery House is said to be in Ashton-under-Lyne, a town some miles away from Ashton-upon-Mersey.

Colin Gresham's papers, including the manuscript of the book, were donated in 1990 to the National Library of Wales.

Art Collection

Romeo and Juliet, by

Ford Madox Brown

From Colin Gresham's notes,

the article in Manchester

Faces and Places, and some internet

searching, we can make a brief survey of James

Gresham's art collection, including works he

presented to galleries. Many of the items at Gallery

House were replicas commissioned from the original

artist, or preparatory studies. Artists are listed

even when no titles of works are known: if you can

add any information about works once owned by

Gresham, please write.

Edward William Rainford: Celia telling Rosalind that Orlando is in the Forest. Attributed to Millais for many years, the work was bought following the 1917 auction by Lord Leverhulme, and remained in his family until sold in 2001.

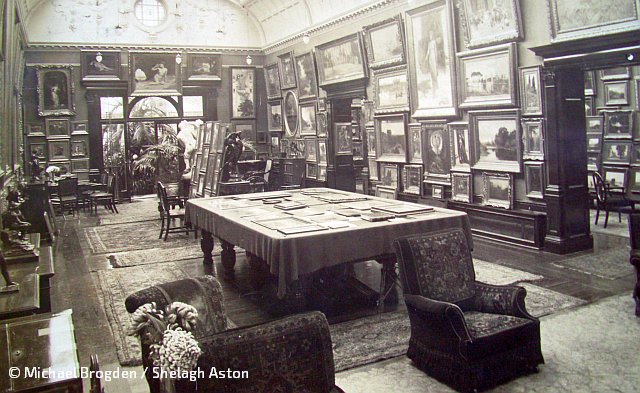

Sotheby's sale record of 2006 related: [In 1902] The picture was sold to a buyer called Shepherd, who was probably also a dealer, and is next heard of in the collection of James Gresham ... Perhaps not surprisingly, [the Gresham collection] was miscellaneous in character, encompassing both early and late Victorian art: Frith, Frost, Cox, Maclise, Linnell and Clarkson Stanfield rubbed shoulders with Albert Goodwin, Alfred East, Edmund Blair Leighton, J.W. Waterhouse, Stanhope Forbes and Lucy Kemp-Welch. The overall tone was fairly academic. Gresham clearly had a passion for Frith, owning an astonishing forty-three examples, while later Victorian classicism was amply represented by a group of major Poynters, including the iconic Cave of the Storm Nymphs (Lloyd Webber Collection), one of H.J.Draper's finest works, The Pearls of Aphrodite (private collection), and the occasional Leighton, Alma-Tadema and Albert Moore. Pre-Raphaelitism, however, was not ignored; there were examples of Madox Brown, Rossetti, Arthur Hughes and Burne-Jones, and in addition to the Rainford Gresham had two genuine Millais, a small version of the 1865 Esther and a watercolour version of one of the artist's book illustrations, The Finding of Moses.

Edward William Rainford: Celia telling Rosalind that Orlando is in the Forest. Attributed to Millais for many years, the work was bought following the 1917 auction by Lord Leverhulme, and remained in his family until sold in 2001.

Sotheby's sale record of 2006 related: [In 1902] The picture was sold to a buyer called Shepherd, who was probably also a dealer, and is next heard of in the collection of James Gresham ... Perhaps not surprisingly, [the Gresham collection] was miscellaneous in character, encompassing both early and late Victorian art: Frith, Frost, Cox, Maclise, Linnell and Clarkson Stanfield rubbed shoulders with Albert Goodwin, Alfred East, Edmund Blair Leighton, J.W. Waterhouse, Stanhope Forbes and Lucy Kemp-Welch. The overall tone was fairly academic. Gresham clearly had a passion for Frith, owning an astonishing forty-three examples, while later Victorian classicism was amply represented by a group of major Poynters, including the iconic Cave of the Storm Nymphs (Lloyd Webber Collection), one of H.J.Draper's finest works, The Pearls of Aphrodite (private collection), and the occasional Leighton, Alma-Tadema and Albert Moore. Pre-Raphaelitism, however, was not ignored; there were examples of Madox Brown, Rossetti, Arthur Hughes and Burne-Jones, and in addition to the Rainford Gresham had two genuine Millais, a small version of the 1865 Esther and a watercolour version of one of the artist's book illustrations, The Finding of Moses.

Alma-Tadema, Laurence:

The Soldier of

Marathon (opus XXX)

Sold by Sotheby's in New York in May 2005 for $192,000, having been owned from 1994 by fashion designer Gianni Versace, who was murdered in 1997.

Bough, Sam: The Bass Rock

Bradley, Basil

Brangwyn, Frank

Brown, Ford Madox: Romeo and Juliet (a version)

Caldicott, Randolph

Cattermole, Charles

Cattermole, George

Cole, George

Cole, Vicat

Constable, John: four pictures including Warwick Castle

Cook, E.W.: The Death of Sardanapalus

Cooper. Sidney

Cotman (?) Seascape and Ancient Building

Cox, David: Twelve pictures including Mill near Lichfield, Lancaster Sands, and The Salmon Trap.

Cubley, W H

Crane, Walter

Creswick, Thomas The Weald

Sold by Sotheby's in New York in May 2005 for $192,000, having been owned from 1994 by fashion designer Gianni Versace, who was murdered in 1997.

Bough, Sam: The Bass Rock

Bradley, Basil

Brangwyn, Frank

Brown, Ford Madox: Romeo and Juliet (a version)

Caldicott, Randolph

Cattermole, Charles

Cattermole, George

Cole, George

Cole, Vicat

Constable, John: four pictures including Warwick Castle

Cook, E.W.: The Death of Sardanapalus

Cooper. Sidney

Cotman (?) Seascape and Ancient Building

Cox, David: Twelve pictures including Mill near Lichfield, Lancaster Sands, and The Salmon Trap.

Cubley, W H

Crane, Walter

Creswick, Thomas The Weald

Dollman, John Charles: Famine Given to

the Salford Borough Art Gallery by James Gresham, 1907

Dicksee, Sir Frank.

Draper, Herbert James The Pearls of Aphrodite

Etty, William: Venus and Cupid

Dicksee, Sir Frank.

Draper, Herbert James The Pearls of Aphrodite

Etty, William: Venus and Cupid

Etty, William: Musidora: The Bather 'At the Doubtful Breeze Alarmed'

Faed, Thomas: Evangeline

Foster, Myles Birket: Landscape with Sheep

Frith, W.P. Derby Day (replica) Manchester Art Gallery

Frith, W.P: Claude Duval

(43 Frith works in total)

Frost, W E

Gilbert, Sir John

Goetze, Sigismund Christian Hubert: "Thy Voice is like to Music heard ere Birth/Some Spirit-Lute touched on a Spirit Sea", Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight. Purchased at the 1917 auction.

Goodall, F

Haag, Carl

Hughes, Arthur

Hunt, W. Holman: The Lantern Maker's Courtship. Manchester Art Gallery.

Kneller, Sir Godfrey

Landseer, Edwin Lassie herding sheep

Leader, B W

Leighton, Frederic

Lely, Sir Peter

Linton, Sir J D

Liverseege, Henry

Lomax, J A

Maclise, Daniel: The Play Scene in Hamlet

Maclise, Daniel: The Origin of the Harp. Manchester Art Gallery

Marks, Henry Stacy

Millais, J E: The finding of Moses

Rosalind and Celia (small version);

Queen Esther (small version); Only a Lock of Hair Manchester Art Gallery

Moore, Albert: Apricots (1866). The property of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, London as part of the Cecil French bequest. Provenance: J.Glover in 1894; J.Gresham by 1912, sale Christie's 12 July 1917 (100) bought Wallis for 90 gns.; J.Croal Thompson, sale Christie's 29 November 1918 (59) bought Connell for 75 gns.; W. Beatson Blair, sale Christie's 20 December 1946 (74 with another) bought Dent for 16 gns.; Cecil French

Moore, Albert: A Garland

Mostyn, Tom: Unsolved

Mulready, William: The Artist's Studio

Nasmyth, Patrick: Near Dulwich

Oakes, W E

Poole, P F

Poynter, E J:

The Cave of the Storm Nymphs . Bought

at the Royal Academy in 1903 for £500, Gresham's

'favourite and most costly picture'. One version later

owned by Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Poynter, E J: Diana and Endymion

Prout, Sam: Chartres Cathedral

Rivière, Briton: Hector lying dead .Manchester Art Gallery

Rivière, Briton: Circe and the Companions of Ulysses

Roberts, David. The ravine, Petra, the Holy Land

Rossetti, D G: La Pia

Rossetti, D G: Washing Hands (water colour study)

Sandy, Paul Derwentwater

Shaw, John Byam

Shields, Frederic J. Factory Girls at Old Clothes Fair, Knott Mill

Simpson, William, The Governor-General's silver state howdah

Spence, T R

Turner, J M W: Bath Abbey, bought from Agnew in 1901

Turner, J M W: Sion, Rhone Valley, bought from the collection of Charles Langton in 1901

Turner, J M W: Verona, bought from Sir Charles Robinson

Manchester

Art Gallery.

Rivière, Briton: Hector lying dead .Manchester Art Gallery

Rivière, Briton: Circe and the Companions of Ulysses

Roberts, David. The ravine, Petra, the Holy Land

Rossetti, D G: La Pia

Rossetti, D G: Washing Hands (water colour study)

Sandy, Paul Derwentwater

Shaw, John Byam

Shields, Frederic J. Factory Girls at Old Clothes Fair, Knott Mill

Simpson, William, The Governor-General's silver state howdah

Spence, T R

Topham,

Francis Williams

Turner, J M W:Laugharne

Castle (watercolour) From the collection of John Ruskin:

discussed in the first volume of his Modern Painters (p.

367-73). Now in the Museum of Art,

Columbus, Ohio Turner, J M W: Bath Abbey, bought from Agnew in 1901

Turner, J M W: Sion, Rhone Valley, bought from the collection of Charles Langton in 1901

Turner, J M W: Verona, bought from Sir Charles Robinson

Wallace, Bruce ("a South

Kensington fellow-student")

Watson, J D

Waterhouse, J W The Siren. Sold by Sotherby's in 2018 for £3,835,800.

Whaite, H. Clarence

Wimperis , E M The ferry

Watson, J D

Waterhouse, J W The Siren. Sold by Sotherby's in 2018 for £3,835,800.

Whaite, H. Clarence

Wimperis , E M The ferry

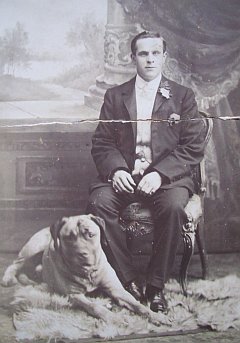

Walter Hall

At the head of the Gallery House team of servants in Edwardian days was a butler, Walter Hall, whose postcards of the house sent to his fiancée Annie Dawson are reproduced here. He his seen above in a studio portrait with the family dog.

He was born in Little Walsingham, Norfolk in 1878, son of the Innkeeper of the 'Robin Hood' inn.

Walter and Annie appear in the 1911 census as a newly-married couple at 23 Eaton Road, Sale. Walter gave his age as 33 and Annie's as 26.

Links and References

Gresham's birthplace, Newark by Phil Gresham

The Avenue and Woodheys Grange, Ashton-upon-Mersey (On this site)

Art Treasures in Manchester: 150 years on by Tristram Hunt and Victoria Whitefield. Manchester Art Gallery, 2007. The book of the 2007 exhibition.

James Gresham and the Vacuum Railway Brake by Colin A. Gresham. Published by Cyhoeddiadau Mei, Penygroes, North Wales, in 1983.

'Mr James Gresham, M.Inst.C.E., M. Inst. M.E., etc.' Manchester Faces and Places, Vol.9 (1898) p. 108-114.

W. Burnett Tracy, and W.T Pike, Manchester and Salford at the Close of the 19th Century: Contemporary Biographies. Brighton: W.T. Pike & Co., 1899. Biography of James Gresham, p.190.

Special thanks to:

Mr Phil Gresham.

Mr James Gresham (great-grandson of James).

The staff of the John Rylands Library, Manchester.

The staff of Salford Local History Library.

Mr Graham Forsdyke of the International Sewing Machine Collector's Society

Mr John Laidlar, Sale local historian.

Mr Michael Riley, Sale local historian

The 'Our Manchester' website.

Ms Beryl Jackson of Islay, for much information about Thomas Craven.

Mr Michael Brogden and Ms Shelagh Aston for the Gallery House images and information about their great-uncle by marriage, Walter Hall.

Comments welcome at

info@johncassidy.org.uk

James Gresham, 1836-1914

Engineer and art collectorJames Gresham, engineer and art collector, counts with Enriqueta Rylands as one of John Cassidy's greatest patrons. He purchased, and donated to the City of Manchester, two of Cassidy's most significant bronze statues, King Edward VII and 'Adrift.' On this page we try to track down Gresham the man, his life and times, and some of his achievements.

James Gresham was born on 28 December 1836 in the house pictured above, 13 Castle Gate, Newark, Nottinghamshire, to Richard and Elizabeth Gresham. He had an elder brother Robert and an elder sister Elizabeth. Richard Gresham was a seed merchant: he died while James was a baby, and his widow Elizabeth later re-married to become Elizabeth Reynolds.

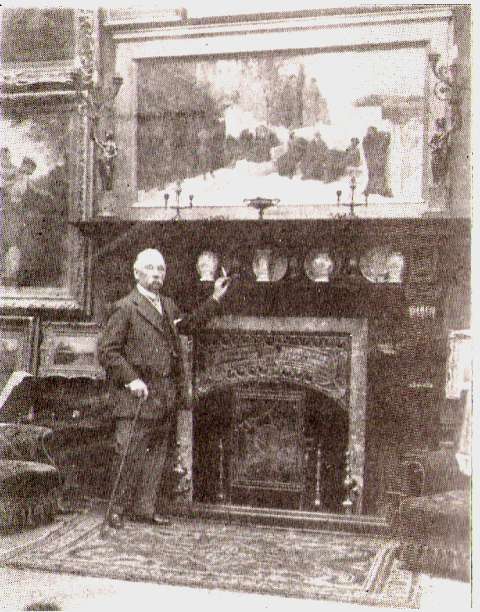

James was educated at the Grammar School in Newark. At the age of fifteen he broke his leg in an accident. It was decided to send him by coach to Lincoln, 16 miles away, for the attention of a bone-setter; unfortunately the coach overturned, and he broke his collar-bone as well as doing further damage to his leg. He was returned to Newark, where a doctor amputated his leg above the knee - most likely without anaesthetic. He was supplied with a primitive wooden leg, which he proceeded to improve upon by inventing an artificial leg which would allowing him to walk almost normally. Showing early business acumen, he sold the design to a maker of surgical appliances.

While restricted in mobility, he took to drawing and painting, and 1855 he headed to London, using the remaining proceeds from the artificial leg to enrol at the South Kensington School of Art. There he met and befriended William P. Frith, today one of the best-known of Victorian artists, for his large works such as 'The Railway Station.' While at South Kensington Gresham came to realise, with advice from Frith and other tutors, that although he was a naturally skilled draughtsman, and excelled at copying the works of other artists - Daniel Maclise was a particular favourite - he lacked the artistic inspiration to create an original painting.

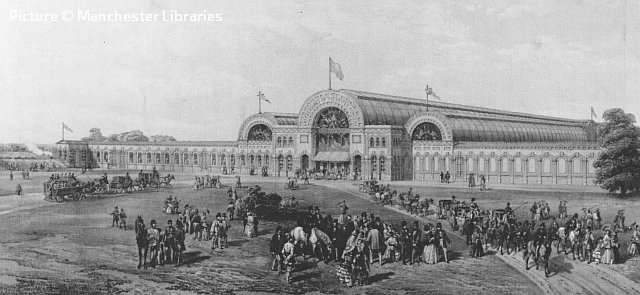

In 1856, he noticed an advert in an art journal for a 'sketching clerk' to assist the secretary of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition to be held in 1857. Seeing the chance of paid employment within the world of art, he applied, and was accepted for the job. He became assistant to George Scharf, secretary to the committee, whom he already knew from his visits to the South Kensington School. (Scharf was the first director of the National Portrait Gallery.)

Gresham's role in Manchester was to help organise the exhibits, and make drawings and pictures of this remarkable event which took place in a specially-built glass-and-iron building palace, covering three acres of the Botanical Gardens in Old Trafford just outside Manchester. Paintings and works of art of all kinds were brought on loan to the exhibition from all points of the compass, often by rail to a station created alongside the grounds for the purpose. The exhibition was open from May to October 1857, and attracted over 1,300,000 visitors. The image above is a monochrome rendering of one of the souvenir lithographs created by Gresham himself.

In 1887, he served on the committee organising the Royal Jubilee Exhibition, which took place on the same Botanical Gardens ground in Old Trafford as the 1857 one which first drew him to Manchester. John Cassidy took part in this exhibition with a demonstration of modelling in clay, and it could well have been here that he met James Gresham, who went on to commission to the tune of several thousand pounds, the two public sculptures. Cassidy created a bronze bust of Gresham, which was shown at the 1904 Royal Academy Exhibition: the present location of this work remains to be discovered. The second Mrs Gresham was also portrayed by Cassidy: the 1911 exhibition of the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts featured that lady twice, as a marble bust and a miniature medallion. Millicent Gresham was also the subject of a small medallion, now in the Manchester Art Gallery collection.

Engineering career

The 1857 exhibition over, and all the treasures returned to their owners, Gresham was in need of another job. He found one at the Atlas Works of Sharp Stewart and Company in Manchester city centre, makers of textile machinery and railway locomotives, where he trained as an engineering draughtsman. While working there from 1858 to 1867, he first turned his hand to improvements in steam locomotive accessories: in particular, the injector, which is a basically-simple device to deliver water into a locomotive boiler under steam pressure without the complexities of a mechanical pump. He also worked on improvements to the company's textile machinery, and designed an improved machine for winding sewing thread on to bobbins.

In 1861, he married Louisa Jane Horseley, a native of Gunthorpe Lodge, Lowdham, in his home county of Nottinghamshire, who is described by his grandson Colin as 'a very strict Victorian wife, who kept her husband and children under firm discipline.' She would have been supported, in the early years of the marriage, by Martha Battle, apparently his wife's grandmother, whom the 1861 census records as living with James and Louisa in their little house at 49 Rutland Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, not far from the Atlas Works. For some reason, he exaggerated his age to the census-taker, describing himself as 35.

In 1865 (or possibly 1867), after an argument with Sharp Stewart over his salary, he left the company and headed off with his wife and two children (Adah and Harry) to London where he worked for a while at the Whitechapel Iron Works, but a few months later he was back in Manchester, where he worked as a self-employed engineering consultant, advising firms and inventing various gadgets including an egg-boiling pan with built-in timer, whilst working on plans to create a practical sewing-machine, an idea he picked up while in London from a man named Ivor Dimmock. The two of them patented a machine in 1869.

Gresham, in partnership with another engineer, Thomas Craven, and a Mr Heron, set up in business as Heron, Gresham & Craven at a factory in Ordsall Lane, Salford, to make the sewing machines and also locomotive injectors. Our picture, reproduced by kind permission of the International Sewing Machine Collector's Society, shows a Model One Gresham sewing machine. This was the first model of the 'Gresham' machine produced by Gresham and Craven in the late 1860s to early 1870s. The cloth plate is stamped Patent March 1867 Heron Gresham Craven followed by the machines serial number. The lever on the base operates the reverse stitch mechanism - a very advanced feature at the time. The base has the monogram H,G,C. The company produced the Improved Gresham - a more streamlined version - in 1873.

The factory in Salford was known as the 'Craven Iron Works' suggesting that a Craven had established it before the Gresham & Craven firm was created. Thomas Craven, Gresham's partner, was born in Manchester in 1850, a son of James Craven. Like Gresham, he had worked for Sharp, Roberts in Manchester. He married Annie Cornforth in 1874, and they lived at 'Merlewood', Chorlton-cum-Hardy near other members of the Craven family. This was a villa in the suburb his family had been was instrumental in developing. In addition to moving into 'Ashleigh' he bought a 'country seat', Kirklington Hall in Nottinghamshire.

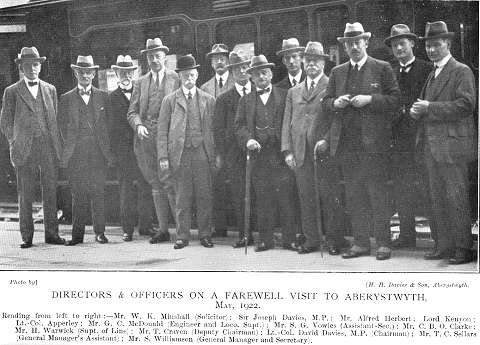

Outside his work with Gresham, in his capacity as Deputy Chairman of the Cambrian Railways company he appears (fourth from right, with stick) in the above photograph, taken at the time the Cambrian sold out to the Great Western Railway in 1922. He was also a director of the Beyer Peacock locomotive building firm. In later years he served as a Justice of the Peace and a Deputy Lieutenant of the County and later the High Sheriff of Nottingham. His wife Annie died in 1902, in 1906 he married a sister of the Countess of Conmel, and joined the aristocracy, with a house in Kensington Palace Gardens. He died in 1933.

By the time of 1871 Census, James Gresham was living at 16 Wilton Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, with his wife Louisa Jane and their children Adah (aged 9), Harry (6), Samuel (3) and Frank (11 months) and describing himself as 'Master Engineer, employing 28 men and 15 boys.' He gave his age more accurately this time, as 35. Now very much of the middle-class, they had a live-in 'domestic servant', Mary Collinson.

Gresham & Craven's injectors were very popular, but they had less success with their sewing machines, eventually leaving the field, after circa 1884, to mass-production makers such as Singer who could bring the sewing machine to the masses. The next development in their range was to be braking equipment for trains, at a time when Government and the public were demanding greater safety on the rails than could be offered by hand-operated brakes.

Mr Heron left the firm due to illness, and the firm took on the name 'Gresham & Craven' under which it became known worldwide. From 1878 they were manufacturing and selling an effective vacuum-powered braking system, which went on, in improved form, to become the standard for most railways in Britain and across the British Empire, against fierce competition from the air-braking system of the Westinghouse company. In 1879 The Vacuum Brake Company was set up in London to market the product, involving Gresham & Craven as well as other brake manufacturers, and this arrangement continued for man years, as the letterhead from 1940 shows. The vacuum brake as applied to steam locomotives creates its vacuum using a device called at 'ejector' which uses steam to pump air out of the system using a principle closely-allied to that of the injector.

The British Film Institute website has a remarkable film clip showing the workers leaving the factory in 1901.

Gresham & Craven also developed, in conjunction with the Midland Railway company, a device which use steam to force sand on to the rails under the wheels of locomotives, preventing slipping, which also proved a good seller.

It was to be the 1960s before British Railways began universal adoption of the more powerful, but more complex, air-brake concept, but not before Gresham & Craven equipment had been used in most of the diesel multiple-unit trains built under the 'modernisation plan' of the 1950s.

The Ordsall Lane works appears to have closed around 1962, after the completion of the diesel multiple-unit contract. The company continued trading from premises in Walkden and later in Cheadle, near Stockport. Eventually, the firm was merged into the empire of their one-time rival, the Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company, but happily, at the start of the new century part of their factory in Salford has been restored as office accommodation, with the name 'Gresham & Craven Ltd' in large lettering visible to travellers on the Metrolink trams, between G-Mex and Cornbrook stations on the north side of the line, although recent building has has partially blocked the view. A nearby development of apartments is named 'Gresham Mill.' The Westinghouse brake business, after several take-overs, is now part of German company Knorr-Bremse.

An engineering firm called 'Heatly and Gresham' is still in existence: this was founded by James's son-in-law Harry Heatly, husband of Adah, and still trades in India where he and Samuel Gresham supervised the installation of vacuum brakes on the railways. For a while in the early 1900s they built motor-cars and taxis back in England under the brand-name 'Rational' but they were not a success. (The London Transport Museum has a picture)

Oak Bank and Gallery House

Louisa Jane Gresham died in 1876; she is, we believe, buried in Brooklands Cemetery. By the 1881 census the family was comfortably established at Oak Bank, 656 Chester Road, Old Trafford, with James's daughter Adah, his son Harry (now a draughtsman with the firm) and Samuel, and his mother Elizabeth Reynolds, now widowed for the second time, attended by a housemaid and a cook. James was not present that day: perhaps he was in London. In 1887, this domestic bliss was somewhat disrupted by James's surprise announcement that at the age of 50 he had married, in London, Helen Amelia Myers, an 'attractive mature woman ... very different from his first wife.' Not only that, they had a baby daughter, named Millicent. A second household developed at Radnor House, 1 Bolton Gardens, South Kensington, London: the 1901 census records James, Helen, Millicent and four servants. (His friend William Frith notoriously had two households in the same area of London.) Millicent later married Walter Jones of Anglesey.

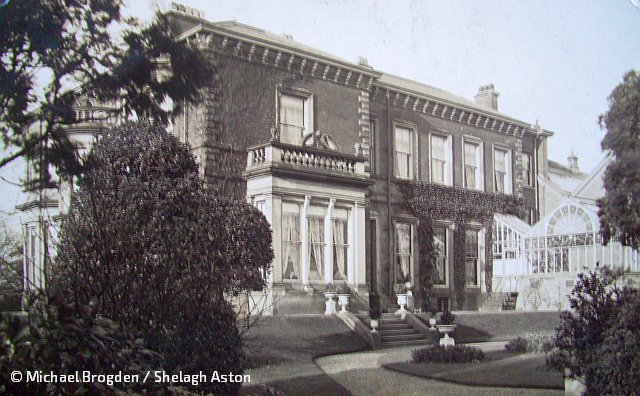

The new Mrs Gresham was not keen to live 'up north' - but some time around 1905 James moved his first family into a bigger house, 'Ashleigh', in Woodheys Park, later known as The Avenue, in Ashton-upon-Mersey, then in countryside outside Manchester (see our page on The Avenue). The house was built for a banker, George Oliver, on land bought in 1871 from William Brooks, a local banker and landowner, and latterly had been the home of Thomas Craven, Gresham's partner. Helen Gresham does eventually appear to have joined her husband there after all the children had left. She is recorded (as Elen Amelia Grasham) at Gallery House in the 1911 census.

Gresham re-named the house from 'Ashleigh' (or Ash Lea) to 'Oak Bank' after his earlier home, and later to 'Gallery House' after he added a private art gallery, designed by architect William Higginbottom of Manchester, who created a number of significant buildings in the Edwardian period, several of which are now listed as of historic interest, including 49, 51-53 and 59-61 Piccadilly as well as Canada House, a large steel-framed warehouse in Chepstow Street, built in 1909. The postcard view above shows the house with a glimpse of the gallery behind.

A postcard from 1910 showing the gallery interior with some of hundreds of artworks; paintings occupy every possible space. Attempts to correlate the works in the image with our listing of known items has proved very difficult (any suggestions welcome) although. the works above the conservatory doors appear to be studies for one of Poynter's 'storm nymph' paintings.

For years Gresham had been collecting paintings, taking care to patronise living artists, especially his friend W.P. Frith, from whom he bought nearly 50 works, including in 1894 a commissioned replica of the famous large work 'Derby Day' which is now in Manchester Art Gallery. (See the left-hand column for more about his collection.)

Gresham's philanthropy also included a contribution to the building of a new School of Science and Art in his home town of Newark, opened in 1900.

'Oak Bank' on Chester Road must have remained in Gresham's ownership, as in 1913 he donated the house and grounds to Henshaw's Blind Asylum, which was based in Old Trafford, as the recorded in the journal The Blind, Vol.4, No.64, October 1913:

Mr. James Gresham, who has been for many years a kind friend to Henshaw's Blind Asylum, has just presented to the Board of Management his late residence, 'Oak Bank', and land sufficient for the erection of commodious and up-to-date workshops. The gift is rendered more valuable on account of its close proximity to the Parent Institution, and the very considerable amount of building materials included. The Board of Management are deeply grateful to their generous benefactor.The house, which was one of several in the area taken over by the Asylum, became the 'Millie Gresham Home for Blind Men', opened in 1914 and named after Gresham's daughter by his second marriage, Millicent. Thomas Henshaw was an Oldham hat-maker left £20,000 to found the charity, which is still active in 2015 under the name of 'The Henshaw's Society for Blind People.' The main building of the Asylum, opened in 1837, and later joined by an equivalent 'Deaf and Dumb' establishment, was an elaborate gothic-style edifice in Old Trafford next door to the Botanical Gardens, site of the 1887 Royal Jubilee Exhibition and an area which Gresham knew well.

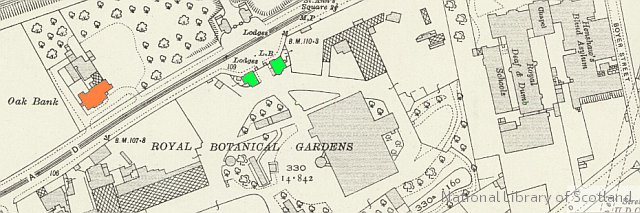

The map extract above dated 1915 shows 'Oak Bank' which we have marked in orange, the Botanical Gardens gateway (still extant in 2019) in green, and the main buildings of the Blind Asylum at the eastern edge.

'Oak Bank' was closed in 1930, in favour of a seaside home in Rhyl. By the 1950s it had been replaced by a large garage building, which still stands in 2015 as part of the extensive Evans Halshaw car dealership. The main Asylum building survived until the 1970s, before being pulled down and replaced by Chester House, an 11-storey block in the modernist style opened in 1979, which housed the headquarters of the Greater Manchester Police. This building had a remarkably short life; the Police moved out in 2010, and considered 'beyond economic repair' it was demolished in 2013. Plans for the site in 2015 envisage it as a car park for supporters attending matches at the nearby football ground.

Death and Legacy

James Gresham died on 13 January 1914, and according to his wishes, was cremated; the ashes were deposited at Manchester Crematorium. His estate was valued at £461,593 (equivalent to over £300 million in present-day values), and his will specified bequests to several local hospitals, as well as the Blind Asylum and Deaf and Dumb school in Old Trafford. His children inherited his shares in Gresham & Craven, where all the sons worked. Gallery House and the paintings passed to his widow Helen - in the case of the house, this was on condition that she promised to live there at least 180 days per year. She declined to do this, and everything had to be sold. She received an annuity, and bought a house in Richmond where she lived until her death in 1918.

His will stated that on his wife's death, or should she no longer wish to live at Gallery House, his trustees might, at their discretion, select such paintings from his collection, except those painted by himself, as they considered suitable, and 'hand them to the Art Gallery Committee of the Manchester Corporation'. A small number of works were so transferred, how they were chosen is not clear. Included was a bronze bust of W.P. Frith by John Cassidy.

The disposal of Gallery House and the art collection was a difficult task in the dark days of World War I. A few remained in the family, but many of the paintings were sold very cheaply at an auction which was held in London over three days in July 1917, featuring no less that 424 lots. The Connoisseur magazine of September 1917 commented on the modern works that 'few ... attained the dignity of three figures.'

Gallery House,with its extensive grounds,was left unwanted: nobody needed such a mansion in the post-war world with its shortage of servants, especially one with an art gallery attached. Ths house and land was sold in 1920 to a local builder called John Edward Dean (in his wife's name) and revived the old name as 'Ashlea'. He did not demolish the house, as we first thought, but altered it by removing the upper storeys to create the bungalow which stands there in 2020, occupied in its early days by J.E. Dean's son Harry and his family.

Further alterations have been made by subsequent owners.; the images above is from a 2019 sales brochure. The straight footpath on the eastern boundary became a street called 'Denesway' (after Mr Dean) on which he built a row of bungalows and the curving drive to the house from The Avenue is now a wooded cul-de-sac named 'Moorwood Drive'. The art gallery was demolished, but a 'coach house' in what was the garden, survives,

Of the other three houses known to have been home to the Greshams: Rutland Street and Wilton Street both were virtually obliterated by developments in the 1960s, although Wilton Street has recently re-appeared in a rather different form as a walkway on the University campus.

And yet - memories of James Gresham remained in 'The Avenue'. Some buildings survived demolition; a terrace of three cottages, given the numbers 7,9, and 11 Moorwood Drive, and a single dwelling numbered 13, appear on a 1956 Ordnance Survey map. At some later date the terrace was demolished, but the single cottage, renumbered 7 and named 'Gallery Cottage' survives in extended form in 2019. 'Galleries Cottage' was recorded in the 1911 Census as home to the Gresham coachman, Frank Knight, his wife Elizabeth and their children Lillian and Cyril. Another cottage was home to their gardener Henry Higson and his wife Hannah.

An old outbuilding, the coach house, also still stands, now at the end of the gardens of two houses in Denesway. It appeared to be in poor condition when we visited in 2009 (above) but by 2019 it had been subject to a makeover. . The gateposts at the start of the cobbled drive still stand as a memorial to Gresham and his private art gallery.

A last view: the author at James Gresham's gateway in 2009. If you can add anything to this story, please contact us.

Written by Charlie Hulme, March 2009. Last updated November 2020.